制造商零件编号 SC1223

RASPBERRY PI CAMERA 3

Raspberry Pi

We're taking on our community's most requested project, Fallout's Power Armor. If you're just joining us now, be sure to go back and check out the first three installments of our Power Armor build!

Episode 1 set the stage and built the base structure for the body and arms

Episode 2 saw the assembly of the upper body, ground support station, and integration of a rudimentary compressor and tank system to make it all somewhat portable

Episode 3 focused on building our most advanced heads-up-display yet, with AR glasses, thermal, infrared optics, biosensors, and every other tool for a wasteland hero

And in our latest episode, we've taken on building some real-world usability into the suit.

Of course, to build any of this, we've needed a model of the armor as a whole, and ours is available for download on https://thangs.com/designer/Hacksmith/3d-model/Fallout%20Power%20Armor%3A%20%28In%20Progress%29-1161815 - fully 3D printable for cosplay!

In Fallout, a suit of power armor is fuelled by a Fusion Core, a handheld nuclear fusion reactor providing immense power and energy density. These were ubiquitous in civilian and military use before the nuclear apocalypse, powering cars, ships, and factories.

In the real world, controlled nuclear fusion power is barely possible, let alone convenient and portable, so our machinery needs to run on more contemporary supplies. The pneumatic systems of our power armor rely on a supply of 150psi compressed air. On the workbench, this can be provided by an air line running from the shop's air compressor to the 12L reservoir tank on the back of the suit. For operating further than a hose's lengths from the shop, the system was equipped with an electric air compressor running off of lithium polymer (LiPo) batteries to produce a portable supply of compressed air, providing several minutes of additional runtime.

Several minutes will not get you far in the wastelands.

Regrettably (although welcome for safety), the energy density of LiPo batteries (~0.24 kW hr / kg) is nowhere near that of nuclear fusion fuel (~100,000,000 kW hr / kg). Carrying hydrogen fuel with a fictional lightweight fusion reactor gets you unbelievably more range than we can manage with a similar weight of batteries.

Lucky for us, we do not need four hundred million times more range. Gasoline, or petrol, is our modern world's ubiquitous fuel source, and it packs roughly 12 kW hr / kg. A gas engine only recovers, if you're extremely lucky, 50% of this energy as useful work, but that still represents 2400% more energy carried per pound than batteries.

To increase our operating range, we installed a 2-stroke engine with an integrated generator. This provides enough power to recharge the batteries even in the face of maximum load from the compressor and auxiliary systems.

To keep noise levels down - a 2-stroke engine is not exactly the picture of stealth! - the engine is only operated when the battery charge level falls too far. A relay in the Kunbus Revolution Pi PLC is controlled based on the 48V bus level, triggering the starter motor or kill switch for the engine to start or stop the flow of additional energy.

Another easy way to increase runtime is to focus on efficiency. To this end, the brushed DC motor on the air compressor was swapped for a brushless DC motor controlled by a servo driver from ODrive, increasing its efficiency and power while also allowing for variable speed operation of the compressor to reduce noise.

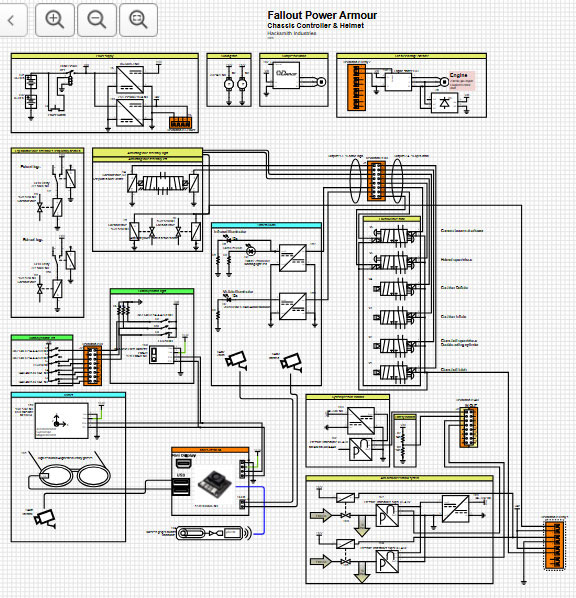

Ultimately, the power architecture for the entire suit was rebuilt from the ground up. The original 24V system was backed by two parallel 6-cell LiPo packs. These are now wired up in series to back the 48V rail, which is attached to the ODrive on the compressor, the range extender generator, and a set of high-current DC/DC converters that supply the 12V and 24V rails with up to 50A each.

The 24V rail supplies the KunBus Revolution Pi and its IO cards, and most of the valves. The 12V rail supplies the Jetson NX, and with it, the heads-up display, lighting, and ancillary systems running on 5V via smaller DC/DC converters.

It's all a bit tricky to describe in words, so check out the visual version of the full schematic diagram:

Power Armour (Part 4) Scheme-it

Power Armour (Part 4) Scheme-it

This has all gotten rather deep into the weeds of how to power a mech suit, but then you've gone through the effort to hunt down the juicy details in an article linked in the description of a YouTube video, so you're welcome. But let's look at another problem that had to be taken on that's more a matter of finesse than power:

How does the computer know when and where to move the arm?

In the earlier videos, the valve controlling the bicep/tricep cylinder was manually operated with a 3-way switch for "up", "neutral", and "down", with a second switch controlling whether "neutral" would allow for free motion of the arm or a locked and held position. This was good enough for a prototype but is so far detached from how the wearer of the suit would typically make their arm move that it would be painfully awkward to use.

We need a control technique that understands the motions that a user would typically make when not wearing two hundred pounds of aluminum, steel, plastic, and gasoline. In principle, this is simple enough: if the user raises their arm, raise the exosuit's arm to match. But directly measuring the motion of the arm is tricky inside the confines of the suit, which uses inflatable padding to keep the user's arms snugly nestled within.

The trick lies with the padding itself. The top and bottom of the forearm each contain a separate inflatable bladder. Though these two are inflated and deflated in unison by the same valves, they can be isolated from one another with another pair of small valves, and a pair of high-resolution pressure transducers - one of many ancillary systems running off of small 5V DC/DC converters - can detect changes in pressure within each bladder.

An increase in pressure on the top bladder corresponds to the users' arm pressing against the top of the arm, suggesting they want to move their arm up, and vice versa. As a bonus, this doubles as a system to respond to impacts and external forces - when an external force pushes the exosuit arm down, a pressure increase will be observed in the top pad as the wearer's arm's inertia squishes it, leading to a command to raise the arm and counteract the force. This ultimately provides closed-loop proportional force control to the user by attempting to counteract any force detected on the user's arm.

Even with a fancy feedback loop, the user can still have switches hidden inside the handholds to deliver extra power or let everything go loose - not to mention to deflate the padding and open the exosuit!

We're starting to near the finish line, so subscribe and tune in next time to see the Fallout Power Armour come together!